INTIMACIES: A silver spiderweb of time

Sarah Vaughan sings Gershwin in a concert: "life is easy" she changes, spontaneously, in "life is difficult". Audience approves. It is 1973, behind the singer there is already a divorce, few years earlier she adopted a little girl. The song is carrying her, breaking her, sweating her out, but the audience is young and cheerful. Voices restlessly intervene in the song and the singer stops. She looks at them; make them quiet with a whisper and her finger at her lips: "watch me, look at me". She explains that the cameramen are having hard time, we are all having hard time, she says, she would rather be in home on her couch, but let us.... and she sings on, breaking down, trembling... repeating and varying the lyrics: "daddy, mama"..."Your Daddy's rich and your Mama is good lookin'..."Audience is forgiving, people follow, and gazes are balancing around the edges of a small podium, songs carries on. Intimacy appears here as a third vocal cord, a device of discipline, a gentle blackmail, but also the openness to empathy. Tacit agreements about tenderness keep all the membranes tensed and all the borders fluent. The intimacy and the public are sharing this small podium: home couch on this podium is both a mental soother and a threat.

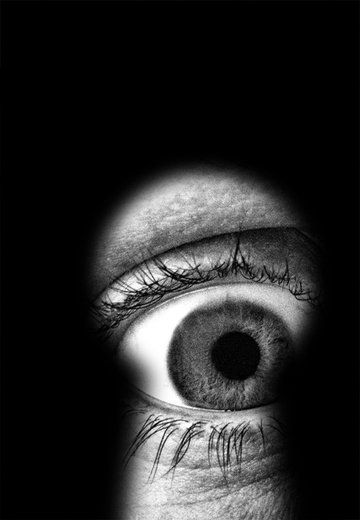

Incurable romantics will often see intimacy as a page in someone's diary, tears spilled at that couch, a hidden cartography of love, entirely behind the scene. The logic of intimacy is, nonetheless, not concerned with details of some contents – be it banal, deep, anal or enamored – its zone is a thin line between the gaze of a diarist and the gaze of his/her neurotic parent that will find the diary under the bed and, secretly, read it. Without gazing by others in front of which one locks the lock on a diary, there is no fortress of intimacy. Locks are important: intimacy is dreamt about behind them, but is also performed through them. In that performance the boundaries of intimacy move like young spring spiders on the long silver threads. Digital intimacy shows those threads on the screen: all touches and lovemaking in the cloud, space suspended between sky and earth, packed with old passions, old fears.

People still write the intimacy, but often within the immediacy of the public. Some Asian girl published her intimate diaries on Internet, while complaining, apparently entirely convinced and honest, about the pain and disturbance of being read "by some, out there." Is she deranged, this poor thing? Or there is some deeper understanding in place here, of the penetrative gaze nobody can escape, an ear opened to the real logic of intimacy. Mourning the lost intimacy is an important ingredient of this logic. Isn't, finally, exactly this publication of intimacy presenting to us the very paradox that marks and inspireswriters from the time immemorial?

Locks we see now, instead on the paper diaries, on the bridges of touristy destinations: there, they publicize someone's "eternal" intimacy. They remind us of the unnatural sin of monogamy and of the myth of chastity belts, especially as they rust and fall apart. On some bridge in Ljubljana, Slovenia, among these locks one can see a pair of dirty underpants firmly tied in a knot. This is, apparently, that half-secretive intimacy that used to be promoted by the falsely liberated magazines for Yugoslav female adolescents: genital privacy, superficially non-pornographic. Letters from readers, nights of insomnia: "I took a bath with my boyfriend, am I pregnant?" Female suffering publicized and disposed of, as always, in the assemblage of love and fear. Her darling is, meanwhile, enjoying systemic fruits. The patriarch is busy, he needs to measure things. Around him the silk thread of intimacy is woven, the one he manifestly and grumpily rejects, even if he doesn't really find it repulsive. Silk threads are knitting the cocoon that Plato called chora, life-giving interval, the interstice. To generations of philosophers, especially female ones, chora was more important than the shared political public of agora. To the archaeologist chora remains simplythe suburbia of polis, a half-systemic situation, often a cultivated field – future Roman ager. Really: intimacy, or better – intimacies, are invoking the image of thefield beyond the wall, the space of culture that accommodates nocturnal secrets, underground germinations, Andersen's Ida dreaming of flowers, Mediterranean passions in dark alleys, anything really. To use the language of Harry Potter: it is the "chamber of secrets" (revealed) and the "room of requirement" in one.

Intimacy is such, gentle and tiring, navel of the home and the world. In fractal arrangement of possible worlds it is not different for Nora, or for Tessa, or Ana Karenina. Field that, by night, welcomes hungry moles and lustful lovers, with first rays of sunshine remains at the reach of guard's gaze. The pressure of the gaze is unbearable, it provokes the raise in page numbers of Russian novels and the numbers of people under the trains, amount of tears per reader. Intimacy is a heavy burden. There is, all of a sudden, the abundance of it, once it's gone with daylight. It gets revealed and publicly denounced: intimacies are most intimate when they are under suspicion, dressed in white aprons, or spread on Oprah's couch. Intimacy is the legal currency of spectacle. It getsused as a payment for those proverbial fifteen minutes if one didn't have that"something" to him/her, or taken as a fine from those that got their fifteen minutes because, allegedly, they were not without it. That is why people crave the brand of intimacy not available to them; intimacy is sold in bulk, or, more often, neatly packed. As some "dinner for two", the "family pack", a travel to unknown, a look upon the life we don't have but that we could, maybe, once, own (limitations apply; while stocks last). To dream these neat intimacies is to cry the overpopulation, surveillance and poverty.

Although the intimacy is often said to be intimate (familiar, known, at hand, homely and "mine"), its fuel, especially in literature, is not made of happy tears. It is rather heimlich that runs into unheimlich, the creepy and twisted return of what needed to be our warm masturbatory corner. Intimacy is conspiracy of the conspiracy theories: fantasy of the communal turned inside-out like a sock. Intimacy is, in a way, writing of the life inside-out, but even its most typical forms need more than a single agent, and regularly more than two single agents. Some of the most solitary cultures invented some of the most closed visions of intimacy. That is why for some classes the most apparent intimacy remains the therapeutic and invasive one – the intimacy of chemotherapy, psychotherapy, physiotherapy, and, soon enough, gene therapy. The latter will, undoubtedly, be the most intimate. Literature is often revisiting these dimensions, with authors agreeing to the direct probing, the analysis of the scalpel, despite words being too stiff, like a surgical thread that stitches the wound but also irritates, inflames, leaving scars.

Of course, inside of us, there is still some tender love for propaganda delivered gently: for the patriotic chants, flower power orgies, soft lullabies. Who could ever take that from us? Literary critics, which on our behalf despised the "intimistic" poets? Or those poets themselves? One of them talked about intimacy as the forced exile, about arranging things in his attic and counting stars while being very careful. Careless words could reveal him, blacklist him, and cut his leash. It is much better, then, to cultivate the nocturnal field. Literature never forgets the imposed intimacies, postcards from forced vacations. Intimacy is,therefore, a political toy as well: liberty, yes, but diminutive. Intimacy is sweetness from "home sweet home", freedom the size of a lapel pin. Its message protects from a direct clash, but the pin can puncture one's skin. And times change: what was a golden pin can turn out to be a thorn in one's eye, in the flesh. Even in the shortest temporal range, the time of intimacy is not in itself, it is also always aboutregretting over that, despisingthis now, dreaming about maybe. Cinematic heroes and theoretical halfwits are sharing the same dream: "We'll Always Have Paris", the past, present and future in one leap and one fall.

Still, not all historical times were obsessed with intimacy. What comes to mind is Virginia Woolf describing in her marvelous Orlando the onset of the 19. Century as a motif of clouds, rain and the growth of the moist, soaked world. Escaping this humidity, families retreated from the vast fields to the cushioned enclosures, ribbons, needlework, baked goods. "Don't touch anything!" Season of the rain brings the rot and the beautiful blooming, hand in hand. Yet, it generates the puritan fear of the ape. Really, aren't we today, as notorious New Victorians, sentenced again to cushions and ribbons of our own transparent and neatly dry intimacies? To the home of our haunted and sold-out bodies the warmth returns as a dry air of the air conditioning, oureyes are not ready for happy tears, thirsty, craving artificial moisture.

Microchips implanted to our body are even more intimate than the inmate's digital bracelets. They already oversee the movement of dogs and Japanese elderly: either group of creatures could, clearly, wander away. Microchipping of the flâneur follows. Who will guard the wandering of us, the privileged ones, in the world that stops us, that tails behind us?Unlike these subcutaneous devices, books willnot measure our movement, won't determine the blood glucose levels or congratulate birthdays, but they can finish built into our lives as a good measure of wandering. Intimacies guarded by books are the silver thread between possibilities: the undone cushion edges, the unfolded silk ribbons, an embarrassing run in one's pantyhose, the fallen zippers.

We shall vacation in this winter of Pula with such unbridled intimacy of the books; we shall wander and move about between colorful titles. Catch the whiff of recently printed pages, greedily, hastily, breaking them like adolescent hearts, inviting them to private tea parties, in our beds, and, certainly, on our exhausted couches. Second hand books we shall smell more carefully, wrapping them in paper, assuring that their "then" and our "now" converse in apparent peace. We will listen to those that carried all these books behind their navels and that, allegedly, know everything about them, ultimately betrayed, as books "happen" to them. Intimate (hi)stories are often traitorous: not as much the evil narratives, as a lovely cliché: a child that opens the doors of an untidy room to the gaze of the unexpected guests. In the winter of Pula we shall dream with this child, of our long lost summers and those springs that are yet to be, apparently. We know already, that this is our "intimate right", our "obvious" capacitynot to be touched, our warm sock and dried-out heart, traces in snow and lost mittens. These are our lives ruffled up, our family treasure: intimately ours, the silver thread of Time.

A. P.

.jpg.360x0_q85.jpg)