Miodrag KALČIĆ

“PULA IS CROWDED” OR THE TOO HEAVY LOAD OF THE PAST ON THE CITY’S FRAGILE BACK

Pula’s complex, layered, oscillating, too comprehensive and long history (three infinitely long and difficult decades of unrest, chaos, disharmony and conflict), powerfully felt (everywhere) and omnipresent, is more of a burden to it (or better yet, her – Pula – a rare female city!), an indescribable urban strain, a kind of ballast, historical pollution (smog of the past), than a dimension of urbanity. Since forever a military city (a veteran Roman colony), its important component of origin, appearance and urban thrive are today annihilated (empties garrisons, military academies and schools, barracks with no sailors, soldiers or officers, and all other accompanying contents: a square, cafés, inns, wineries, dances, cabarets, brothels, cinemas etc.); demilitarised and unrecognisable, it is trying to bring (because, after three thousand years of survival, it is doomed to persevere), no matter how stupid, silly, pointless, paradoxical or abstract it may sound, the contemporary historicity of the disconnected past back to life. An important, significant and crucial fragment of the history of Pula is its Austrian-Hungarian episode.

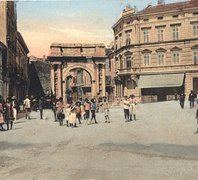

Shielded by the umbrella of the Austrian-Hungarian Monarchy, Pula became a city again, just like it was long time ago in the Roman era, and as a growing and developing urban and military-naval centre of the Austrian Empire (Cisleithania in Austria-Hungary) it thrives in all respects. Austria gave Pula back its life, safety, work, residence, education, health care… and the most important quality: contemporariness and urbanity, culture and art, leisure and entertainment. The military-naval orientation and (war) shipbuilding greatly determined Pula’s specific urbanity. Port admiralty data from 1908 show that only 36 per cent of Pula’s citizens ‘are not directly supported by the army’ and that ‘the army is financing 75 per cent of the Pula municipality revenues’, testifies to the enormous role played by the army in all urban aspects. Thanks to the military empire of the Austrian naval fleet in Pula, its identity and the status of a growing European city was almost completely determined, together with all the development (and unplanned) plans for accelerated urbanisation.

Pula’s demographic explosion is incomparable with all other Croatian and most European cities. Between 1848 (around 1000 citizens) and 1910 (58,562 citizens, of which 16,014 military people), i.e. in a period of 62 Austrian years, the number of Pula’s citizens increased 53 times, or the stunning 5,280 per cent. Five largest Croatian cities registered a significantly lower population growth than the fascinating Pula: Zagreb 367 per cent, Rijeka 324 per cent, Zadar 217 per cent, Osijek 205 per cent and Split 197 per cent. The expansion in population and economy was, naturally, accompanied by residential construction: from meagre 214 buildings in 1842, in 1910 the municipality of Pula had 6346 contemporary buildings, institutions, houses, villas etc., not only in and around the centre, but also in neighbouring contradas becoming the suburbia: VeliVrh, Kaštanjer, Šijana, Vidikovac, Sisplac, Veruda, Stoja, Valmade, Valdebek etc.

As a Central European, Mediterranean (more geographically than substantially), but first of all a military-naval city, Pula was ethnically, civilisationally, culturally, linguistically and in many other aspects an utterly heterogeneous community. Cosmopolitan leaning and multiculturalism, which are too often unjustly and over-affirmatively implied and positively accepted (and regarded), in Pula’s case are more a delusion than a quality, because in no way do they stand for peaceful coexistence and harmonious tolerance among the multinational population. Quite often (therefore, frequently) this unprepared, inappropriate, sudden and forced multi-ethnicity was the source of many political tensions, social misunderstandings, cultural misconstructions and other conflicts, of which there was no shortage in Pula, quite the contrary.

However, the people of Pula and their navy led peaceful lives (walking along the corso and riva), in merriment (at cinemas and brothels) and joy (at cafés and inns), all until late in June 1914. Early in July the same year, the Minerva cinema stopped showing ‘tolerant little films’ and turned to serious documentaries: Funeral of Archduke Crown Prince and Countess of Hohenberg and Sarajevo Drama, portending the uncertain future of the Monarchy. World War I officially began exactly a month after the ‘young Bosnian’ Sarajevo Drama; on 28 July 1914 Pula’s church bells signalled Austrian-Hungarian Monarchy’s announcement of war on the Kingdom of Serbia. A few days before, anticipating the Austrian-Hungarian pride, a partial conscription of male population took place.

The war was sensed on 13 August, when the passenger ship Baron Gautsch, sailing its regular line Trieste-Kotor-Trieste with 246 passengers (children below 10 and military conscripts were not on the passenger list) and 64 crew members stumbled on an Austrian naval mine seven miles north-west offBrioni and sank. Soon afterwards, on 23 August, the torpedo boat TB-26 came across a mine (again its own, Austrian) and 11 crew members lost their lives. Naturally, the news was never published in either Pula’s or Austrian newspapers. Merchant steamship Josephine sank for the same reason on 17 November, 10 miles off the coast of Pula. Finally, on 20 December, a French submarine was caught in an anti-submarine net just outside the port of Pula, and when it dived up it was sunk by two war vessels from the port. The submarine was later repaired and included in the K&K fleet. In October 1915 lieutenant commander Georg Ludwig von Trapp was appointed the submarine commander; his numerous family lived in Pula for a while.

Cannon firing and the enemy before the port signalled to all the people of Pula that the war came dangerously close to their city. When Italy announced war on Austria-Hungary, on 23 May 1915, a curfew was placed and on 10 June the municipal administration was suspended. Count Rudolf von Schönfeldt took over the power as the imperial-royal fort supervisor or, more commonly, commissary. Fifty thousand soldiers came to Pula and the region, mostly conscripted in Istria. After a short training they were assigned in military units in Serbia, Bukovina, Galicia, on the Sočariver… In strict wartime conditions the works discipline was also made stricter. The fear of a direct attack on the city drove the people of Pula in the first (out of three, often forgotten) exodus. All population from the city and its surroundings unneeded and unfit for work and war (primarily women, old people and children) was removed. Around 12 thousand civilians remained in Pula. Citizens of Pula and the region were evacuated (in May and June 1915) to (unsuitable) detention camps in Austria, Hungary, Moravia and Czech Republic. It is estimated that over 26 thousand people were evacuated; half of them returned late in 1917 and in 1918.

Between 9 December 1856, when Emperor Franz Joseph laid foundations of the future European city on the Roman ruins, and 20 December 1914, when the French submarine got caught in the anti-submarine net off the port of Pula, signalling the real beginning of World War I in Pula, for 58 years (and 11 days), Pula persistently, constantly and rapidly grew, developed to become an urban entity, a recognisable, exceptional, cosmopolitan, particular, Mediterranean/Central European city. It was precisely in late 1914 that it reached the pinnacle of the identity of its own perseverance, its specific peculiar independence as only very few European cities could. The Great War destroyed the city, ruined Pula, leaving only contours and shadows. The later diverse and complete identity of Pula, a city of unacknowledged age and senseless youth, is a mark of the Austrian-Hungarian past, a historical trace of constant melodramatic oscillations between urban constructions and destructions, gradations and degradations of all kinds of urbanities (both actual and artificial), rare oases of civility, Pula’s shadows of identity, pleasure of its own shade.

In Pula, a tender military city of a female name, with an overbearing burden of the past on the city’s fragile back, almost everything already existed, everything happened, everything took place, everything took place before, before we knew… only because of Austria, the Austrian-Hungarian Monarchy and a bit of historical coincidence.